The benefits of data opening for both science and society have been widely exposed. Data sharing not only helps making research more sustainable but also accelerates innovation, and Archaeology is not an exception. In fact, the openness of Archaeology in general and of archaeological research data has been seen not only as a beneficial practice but necessary, as a practically imperative solution to the already destructive nature of the archaeological research method, as well as an ethical obligation for a discipline that studies a public good such as heritage and uses mostly public funding.

In the road leading to open archaeological research data, researchers play a crucial role, as they are the ones who collect, work, and manage the data during most of their lifecycle. Considering this, it feels necessary to assess their points of view, to fully understand how they are managing and sharing (or not) their data, and why. Understanding the researchers’ perceptions and their current research data management practices can allow us not only to get to know the real starting point and evaluate the implementation of open data, but also to define the challenges this new model must overcome and develop a better strategy to foster its implementation.

My study focuses Catalan archaeology researchers, as this region has a dynamic and complex yet well-defined archaeological community that includes more than seven research institutions and nearly 30 research groups. With the goal to get to know these researchers’ practices and perspectives, I am conducting a series of interviews to 40 of the principal investigators of archaeological research projects. During the interviews, topics such as data management practices, data sharing practices, reuse practices as well as opinions around archaeological open data, its possibilities and challenges, are discussed. In this poster, I will be presenting the theoretical background of the study, the methodology applied, the design of the questionnaire, and an overview of the preliminary results gathered up to the moment.

Since 2012, archaeological open data has been an increasingly discussed topic. Most of the literature revolves around defining the main advantages and disadvantages of this model, which act as accelerators and barriers for its implementation.

In 2010, Costello listed the benefits of opening research data, many of which have been repetedly defended and expanded by other researchers:

Added value to research

Possibility to validate results

Prevention of scientifici misconduct and methodological fraud

Help to policy making

More sustainable research

Return of public investment made in research

Return of data to its original place/community

Most of these reasons to open research data are also valid for Archaeology, and authors agree that the discipline would benefit from a greater openness. To these already indentified pros to Open Research data, some more especific have been added (Moore & Richards, 2015) such as the increase of collaboration, the democratization of Archaeology, and the amelioration of the preservation of archaeological data.

However, there are also perceived disadvantages that act as barriers for the implementation of this model. In a systematic review of the open data literature, Chawinga (2019) identified the main barriers to data sharing:

Lack of incentives/recognition for researchers

Potential danger for sensitive data

Lack of time

Fear of losing rights over the data

Fear of misuse or misinterpretation of the data

Fear of losing the scoop

The main goals of this research were:

Assess the current practices of data management, sharing and reuse within the archaeological research projects in Catalonia

Analyse the rationale behind these practices

Determine whether the traditional accelerators and barriers to open data are perceived as so by Catalan archaeology researchers

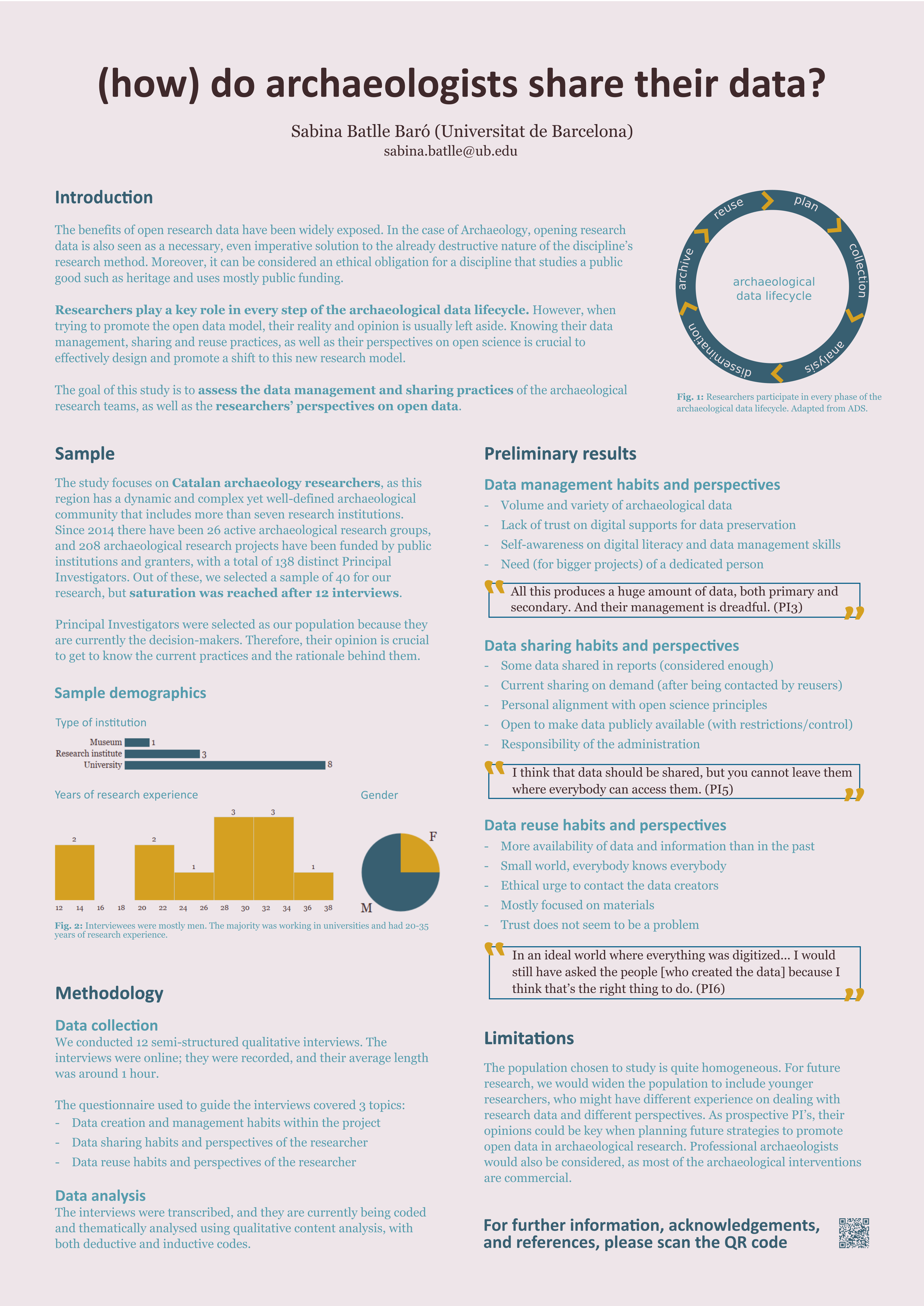

The study focuses Catalan archaeology researchers, as this region has a dynamic and complex yet well-defined archaeological community that includes more than seven research institutions. Since 2014 there have been 26 active archaeological research groups, and 208 archaeological research projects have been funded by public institutions and granters, with a total of 138 distinct Principal Investigators. Out of these, we selected a sample of 40 for our research, but saturation was reached after 12 interviews.

Sample

Principal Investigators were selected as our population because they are currently the decision-makers. Therefore, their opinion is crucial to get to know the current practices and the rationale behind them.

Data collection

We conducted online semi-structured qualitative interviews. The interviews were recorded, and their average length was around 1 hour.

The questionnaire used to guide the interviews covered 3 topics:

Data creation and management habits within the project

Data sharing habits and perspectives of the researcher

Data reuse habits and perspectives of the researcher

Data analysis

The interviews were transcribed, and they are currently being coded and thematically analysed using qualitative content analysis, with both deductive and inductive codes.

Limitations

The population chosen to study is quite homogeneous. For future research, we would widen the population to include younger researchers, who might have different experience on dealing with research data and different perspectives. As prospective PI’s, their opinions could be key when planning future strategies to promote open data in archaeological research.

Professional archaeologists would also be considered, as most of the archaeological interventions are commercial.

This is still an ongoing research, and therefore the results are just preliminary and subject to changes as the investigation continues and concludes.

This research was supported by an FPI grant (Formación de Personal Investigador) from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (MCINN) to Sabina Batlle Baró (PRE2019-091286).

A special thanks to the organisation of DAB23 who gave me the opportunity to present my research.

Aspöck, E. (2019). Moving towards an open archaeology: projects, opportunities and challenges. Mitteilungen der VÖB, 72 (2), 538-554.

Beck, A.; Neylon, C. (2012). A vision for Open Archaeology. World Archaeology, 44 (4), 479-497

Chawinga, W. D.; Zinn, S. (2019). Global perspectives of research data sharing: A systematic literature review. Library and Information Science Research, 41 109-122

Costa, S. (2014). Defining and Advocating Open Data in Archaeology. CAA2012 Proceedings of the 40th Conference in Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology, Southampton, United Kingdom, 26-30 March 2012

Edwards, B. (2015). Open Archaeology: Definitions, Challenges and Context. Open Source Archaeology 1-5.De Gruyter

Kansa, E. (2012). Openness and archaeology's information ecosystem. World Archaeology, 44 (4), 498-520

Kansa, E. C. (2013). On ethics, sustainability and open access in archaeology. The SAA Archaeological Record 15-22

Kintigh, K. W. (2015). Extracting Information from Archaeological Texts. Open Archaeology, 1 96–101

Lake, M. (2012). Open archaeology. World Archaeology, 44 (4), 471-478

Lynam, F. (2016). Untangling the web of data. Acritical analysis of the Archaeological Semantic Web. Department of Classics, School of Histories and Humanities, Trinity College Dublin, University of Dublin

Marwick, B. (2018). A Standard for the Scholarly Citation of Archaeological Data as an Incentive to Data Sharing. Advances in Archaeological Practice, 6 (2), 125-143. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1017/aap.2018.3

Marwick, B.; et al. (2017). Open science in Archaeology. The SAA Archaeological Record, 17 (4), 8-14

Moore, R.; Richards, J.D. (2015). Here today, gone tomorrow: Open access, open data and digital preservation. In Open source archaeology: Ethics and practice, ed. A.T. Wilson and B. Edwards, 30–43. Berlin: De Gruyter Open.

Previtali, M. (2019). Archaeological documentation and data sharing: digital surveying and open data approach applied to archaeological fieldwoks. Virtual Archaeology Review, 20 (20), 17-27

Wilson, A. T. (2015). Open Source Archaeology Ethics and PracticeDeutsche Nationalbibliothek. ISBN: 978-3-11-044016-4